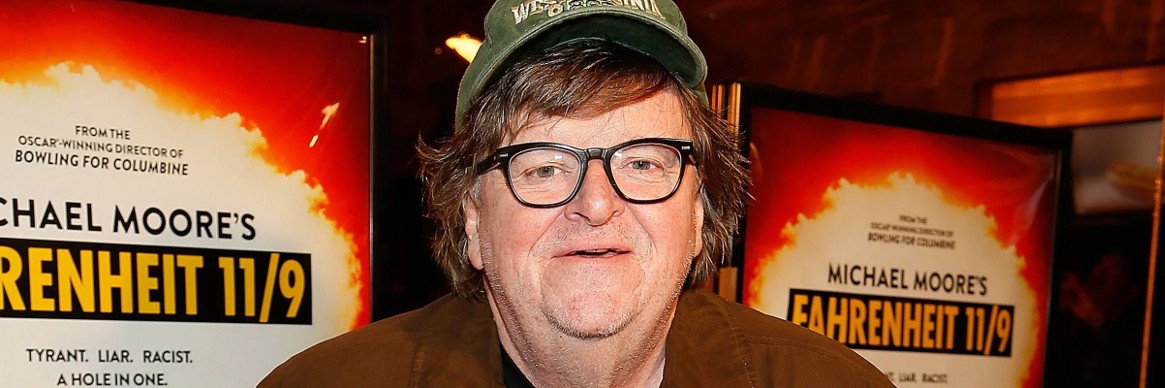

He’s a fat, stinking rich, narcissistic loud mouth with a penchant for baseball caps and demagogy and he’s just made a movie about Donald Trump.

Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 11/9 (the date of Trump’s victory confirmation and a nifty inversion of Moore’s earlier Fahrenheit 9/11) is a chronicle of the decline of left-wing politics in America, represented in Moore’s mind by the triumph of the Don.

The movie opened in Auckland last Thursday to much fanfare. There were three other solo men in the 16 seat theatre for the 9 pm showing. The bloke behind me slipped into a deep slumber thirty minutes in.

I sympathised.

Moore has a limited bag of tricks.

- The darkened, slow-mo sequence, with ominous music making the object of his obloquy look like they’re up to no good.

- The interviews or speeches edited together without context.

- The sarcastic know-it-all voice-over.

- The stunt scene, always involving the people’s hero, Michael Moore himself (in this instance he tries to make a citizen’s arrest of a Republican governor).

- The non-sequitur disguised as an incriminating connection (the centrepiece of the film is a long look at the lead poisoning of Flint, Michigan’s water supply, which is relevant because, um, Trump went there once).

- The sordid ad hominem (Moore suggests an incestuous relationship between Trump and his daughter, Ivanka).

- The simple factual inaccuracy (Moore calls the Electoral College a "concession to slave states" when it was supported by opponents of slavery as well).

- Bonkers evidence-free theories (he claims Trump’s presidential bid was just a strategy to get a higher salary for The Apprentice that got out of hand).

Trump has had a long involvement in politics – he tried to secure the Reform party’s nomination for a presidential run back in 1999.

It’s easy, through manipulative film-making techniques, to make a political figure look like an arsehole. It’s even easier when, in the case of Trump, that figure is, in fact, an arsehole. Moore, however, goes way over the edge in the film’s last sequence, when he overdubs images of Hitler speaking at a Nazi rally with Trump’s voice. The comparison is not only historically inept, it’s also stupid. To take one obvious difference, it may seem trivial but Hitler had no sense of humour. Historian Trevor Roper’s Hitler’s Table Talk, a record of Hitler’s private conversations with his cronies during the war, includes only one rather lame joke. The Don, on the other hand, is funny and is able to make a joke even when it’s at his own expense. Just last month commenting on being a teetotaler, he said it was "one of my only good traits" and "imagine if I [drank] … I'd be the world’s worst."

That kind of self-knowledge should stop any drift into Hitlerian egomania.

The film is most effective when Moore is taking shots at his own side, mocking the Clintons and laying out how the Democratic party machine rigged the nomination against Bernie Sanders. Ironically Moore’s hated Republicans had a much more democratic, diverse field of candidates than his Democrats did.

Moore finds hope in the new breed of hard left Democrats, many of whom are openly socialist. They share many of his obsessions, and the last twenty minutes of the film in which he champions their cause is like a montage of his greatest hits – pieces on gun control, universal health care and empowering the unions.

The film ends with a dangerously ambiguous call to revolutionary action over apocalyptic imagery.

Moore began his career with Roger and Me, a film harshly critical of the effect of globalisation on the American working class. Trump, steward of a booming economy with real wage growth is doing more for these people than Moore’s activism has ever achieved.

In encouraging an overthrow of the system rather than a practical path to prosperity for the impoverished, Moore exposes himself as worse than the guy he’s railing against.